It’s common in digital product design to have an understanding of the varying levels of reliability of the data you get from user research. What users say and do is full of bias and subconscious and unconscious drivers, making it very difficult to take their data at face value. This is the challenge at the heart of any user-centred design process. Frankly, it’s just plain difficult to get under the skin of a problem and understand the ways we can help the people we are trying to design for and with. However, presenting this to the wider organisation is also a challenge. Especially in places where there may be headwinds against human centred approaches. Pointing out the challenge in un-reliable user data — often feeds into the mindset that drives not talking to users.

The unreliability of users is a common risk in product design, and often this is pointed out to counter to the argument from other parts of the organisation, who see research simply as “we’ll ask users, they’ll tell us what they want”.

This in itself is a positive statement of user-centricity, as much as it is a definition of a sub-optimal design and research process. It’s great to speak to users, but the ways (methods) used to do it, the robustness of the data, the quality of the data analysis and synthesis, make it a challenging process to create actionable knowledge to innovate and drive your product and service forward. It can be hard to convince people of the benefits of user-centricity when you are also saying, often immediately, that those people are unreliable witnesses. You’re efforts to advocate user-centricity are subsequently undermined by your suspicions in the value of their data.

This is when some smart-aleck pops up with “Apple doesn’t do research" followed by someone wheeling out the Henry ford quote* (that apparently wasn’t said by Henry Ford) about if he “listened to people, I would have built a faster horse”

To make this conversation go more smoothly, I used a couple of examples to illustrate this problem of unreliability. One of these clearly points out this contradiction, shows the magnitude of the problem, and can help steer the conversation to how design research can be more effectively.

Alcohol to the rescue

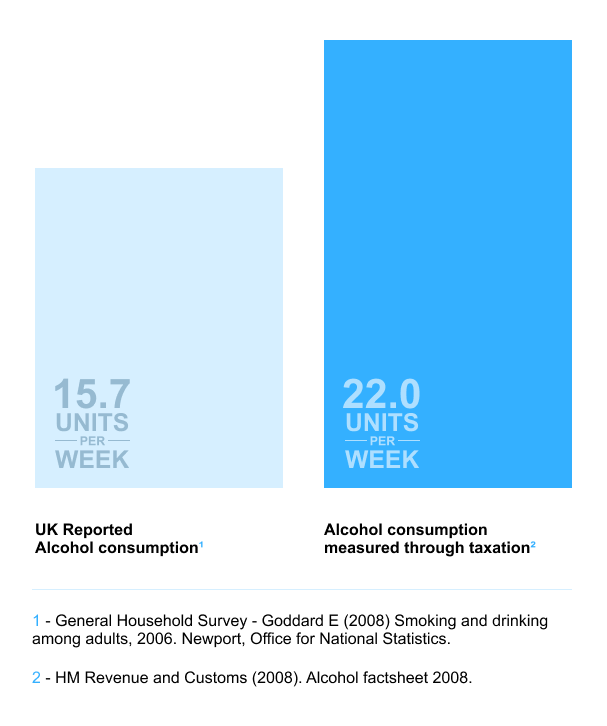

A great example illustrating the differences between ‘what users say and what users do’ comes in the form of alcohol consumption. In the UK, data shows a large difference between actual alcohol consumption and how much people report they actually drink. Luckily, this difference is relatively easy to measure when comparing two different data sources. The 2006 General Household survey (in the UK) reported individual alcohol consumption around 15.7 units per week. This is how much people said they drank. It’s still over the 2 units per day recommendation. However, HMRC (2008) also measures alcohol consumption through taxation — arguably are more accurate measure as it includes all sales (tap beer sold through pubs). In 2008, this saw individual Alcohol consumption around 22 units per week.

This is a 40% increase in consumption. A massive difference between what poeple said they did and what they actually did. Not only does this show that user reported data is unreliable, it also shows the magnitude of it’s (in this context) unreliability.

I saw this first hand at Babylon Health, the design teams I was looking after were focused on our key tele-health platform — connecting patients to clinicians in a digital first primary health care consultation. We needed to maximise the information exchange between patients and clinician. We’d often hear from our Doctors that they wouldn’t trust some patient reported data. As a rule of thumb, any responses to questions regarding as Alcohol intake were often tripled.

This is a great example of the differences between what users say and what users do. Played out in the types of data we get back from our research efforts, and also within the products themselves. It shows that ‘just asking users what they want’ doesn’t work and isn’t enough — they’re not product designers.

Highlighting this issue though, is great in directing conversations within your organisation about the value and shape of design research and user centred approaches in making great products. If user data is sometimes unreliable, but speaking to users is so important, then how do we tackle this.

For me, the most valuable conversations happen when we start talking about wider design and research approaches and the impact that synchronising differing approaches may yield. This moves the conversation away from the challenges of talking to users, and towards how you can synchronise various methods and approaches to best effect. This usually includes discussion around the following:

The importance of varied methods in research gathering.

This is an argument for more research, not less. It argues for a mixed-methods approach, tbut also for more in-depth range of data gather methods. By recognising the challenges in understanding user data, this can be help promote a wider range of research methods and data gathering activities. An over-reliance on semi-structured interviews and can be mediated by introducing activities like diary studies, or simply contextual enquiry. Other qualitative data channels

Why framing is important

It’s not enough to just do a research report. Knowledge from research must be actioned. Moving data to another frame — this means synthesising data into artefacts like Value canvases, or solution tree’s ..or even prototypes (see below) is vital. The storytelling through the narrative framing of data is a powerful tool to help show the path forward for a product

Why building prototypes is important.

This isn’t about building UI but an approach that seeks to research what you make (research through design) to better understand your users. And it’s not about usability testing either, often prototypes are used only for research — tools to help better understand your us

The challenge of unreliable user data in digital product design is not a deterrent but an opportunity for innovation and deeper understanding. The discrepancy between what users say and what they actually do, exemplified by the alcohol consumption study, highlights the limitations of relying solely on user-reported data. This insight is crucial for organizations striving to adopt a user-centric approach, especially in environments skeptical of such methods. By acknowledging the unreliability of user data, designers and researchers can advocate for a broader, mixed-methods approach in research, employing a variety of techniques like diary studies, contextual inquiries, and others.

Moreover, the process of transforming research findings into actionable insights is equally important. Framing data effectively through tools like value canvases, solution trees, or prototypes is vital for guiding product development. Prototypes, in particular, serve as valuable research tools, enabling deeper understanding of user needs beyond mere usability testing. This shift in perspective - from viewing user data as a problematic to an integral part of a comprehensive research strategy - can significantly enhance the effectiveness of user-centric design processes.

Ultimately, embracing the complexity and nuance of user data, and integrating diverse research methods, can lead to more informed, innovative, and user-responsive product designs. This approach not only addresses the inherent challenges of user-centric design but also leverages them as a catalyst for creating more effective and meaningful digital products.

*Ford did say this though

"If there is any one secret of success, it lies in the ability to get the other person's point of view and see things from that person's angle as well as from your own" - Henry Ford